In an “Egyptian-Japanese School” on the outskirts of Cairo, the day’s cleaning is done. The daily class coordinator steps forward, looking slightly nervous, and says, “Everyone worked very hard today. The group that wiped the desks was especially thorough.” The teacher watches over the applauding children with a gentle gaze. Here, Japan’s “Special Activities” are known as “Tokkatsu,” transforming the classroom into a “miniature society.” Why have Japanese classroom activities been introduced in Egypt? The background lies in the profound sentiments felt by a national leader during his visit to Japan, and in the exceptional trust placed in a distant country.

The Spirit of the “Walking Quran” Crosses the Nile

The origin of the current Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) project in Egypt, the “Project for Enhancement and Dissemination of Tokkatsu Model” traces back to a scene witnessed by the Egyptian President during a visit to Japan. During a school visit in Tokyo, arranged at the President’s own request, he observed children in an orderly manner serving school lunch together, without waiting for teachers’ instructions, calling out to each other. “How can children do this by themselves?” Deeply moved by this sight of self-discipline and collaboration, the President praised Japan’s society, which values order and harmony, and reportedly referred to the Japanese people as the “Walking Quran.” The meaning was “people who practice the noble teachings of the Quran in their daily lives.” The desire to have education that bridges ideal and practice in his own country led to a request for Japan’s cooperation.

Responding to this, the introduction of Japanese-style education, which began with two pilot schools in 2015, has seen remarkable expansion. Today, 69 model schools have been established nationwide as “Egyptian-Japanese Schools (EJS).” Furthermore, in a groundbreaking move, “Tokkatsu” has been formally incorporated into Egypt’s national primary education curriculum. All public schools are now required to dedicate 40 minutes per week to Tokkatsu practice. This signifies not merely the adoption of a “Japanese style,” but that Egypt itself has integrated the Japanese educational philosophy into the core of its own education system.

Outside view of an EJS built largely in accordance with Japanese standards

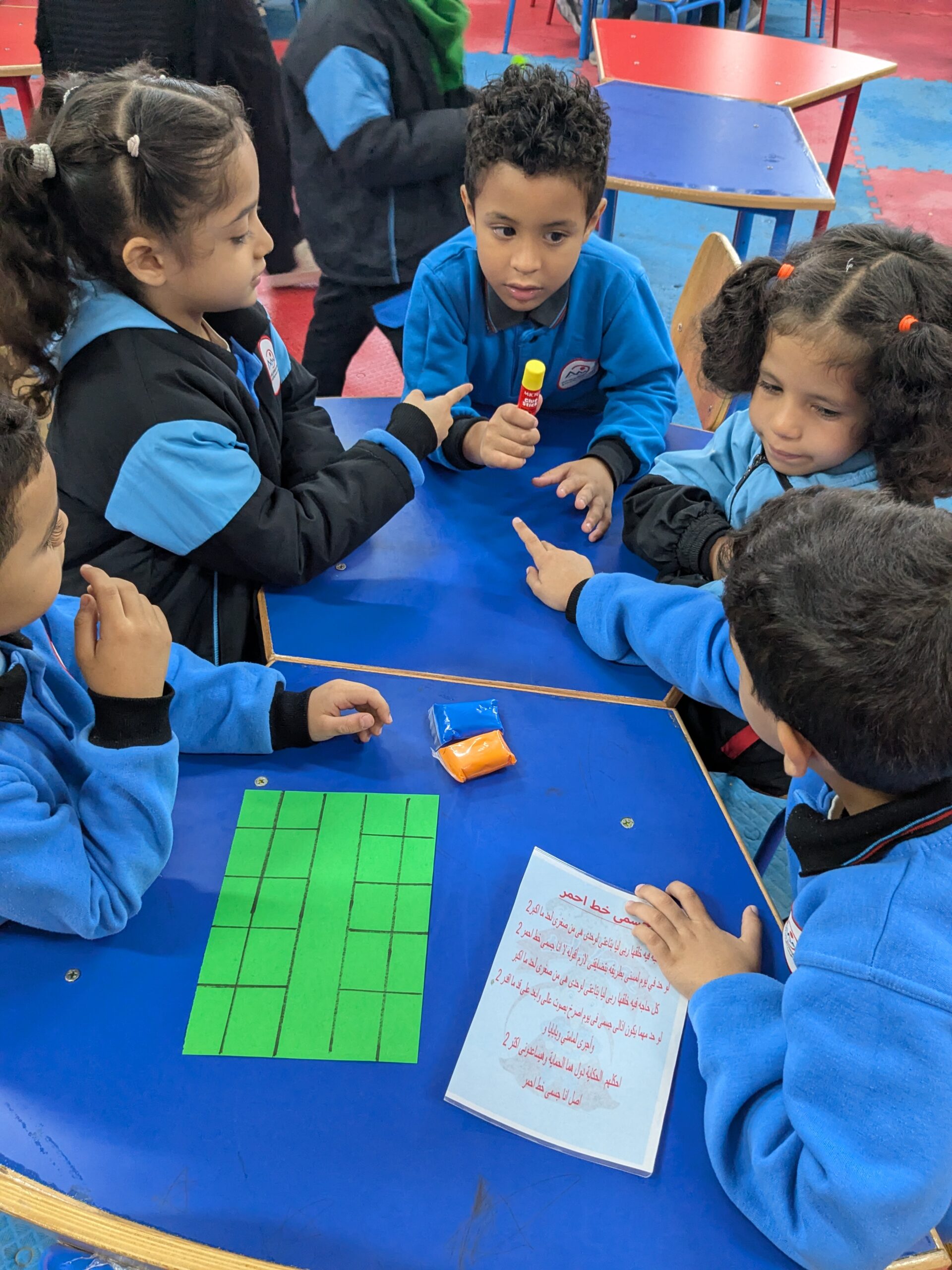

Outside view of an EJS built largely in accordance with Japanese standards The attached kindergarten provides intellectual training based on learning through play

The attached kindergarten provides intellectual training based on learning through play

What Tokkatsu Aims For: A Dress Rehearsal for Good Citizens

What, then, is the essence of “Tokkatsu” that Egypt sought? It is the nurturing of “Life Skills” that go beyond reading, writing, and arithmetic. It views the school as a “miniature society” and a “practice ground for becoming good citizens” before entering society. Its essentials are condensed into three main practices.

First, Daily Coordinator (Nicchoku). This is where all students take turns learning through experience that leadership is not a privilege but a responsibility, and that excellent organizations require both good leaders and good followers. Equal opportunity builds the foundation for mutual understanding.

Next, Class Discussion (Gakkyukai). Students discuss familiar issues like, “How can we avoid fights over how to use the schoolyard during break time?” aiming to improve their own school life by themselves, without relying on the teacher. They learn to assert their own opinions, listen to differing views, and reach a “satisfactory solution” through dialogue and creativity, not merely by majority rule. This experience becomes the driving force for citizens who will actively shape society in the future.

And finally, Cleaning (Seiso). This is not merely a beautification task. It is the practice of “belonging and contribution,” where students concretely demonstrate the responsibility they naturally bear as members of the community (their classroom) from which they benefit. Through this, a sense of public spirit and agency is cultivated.

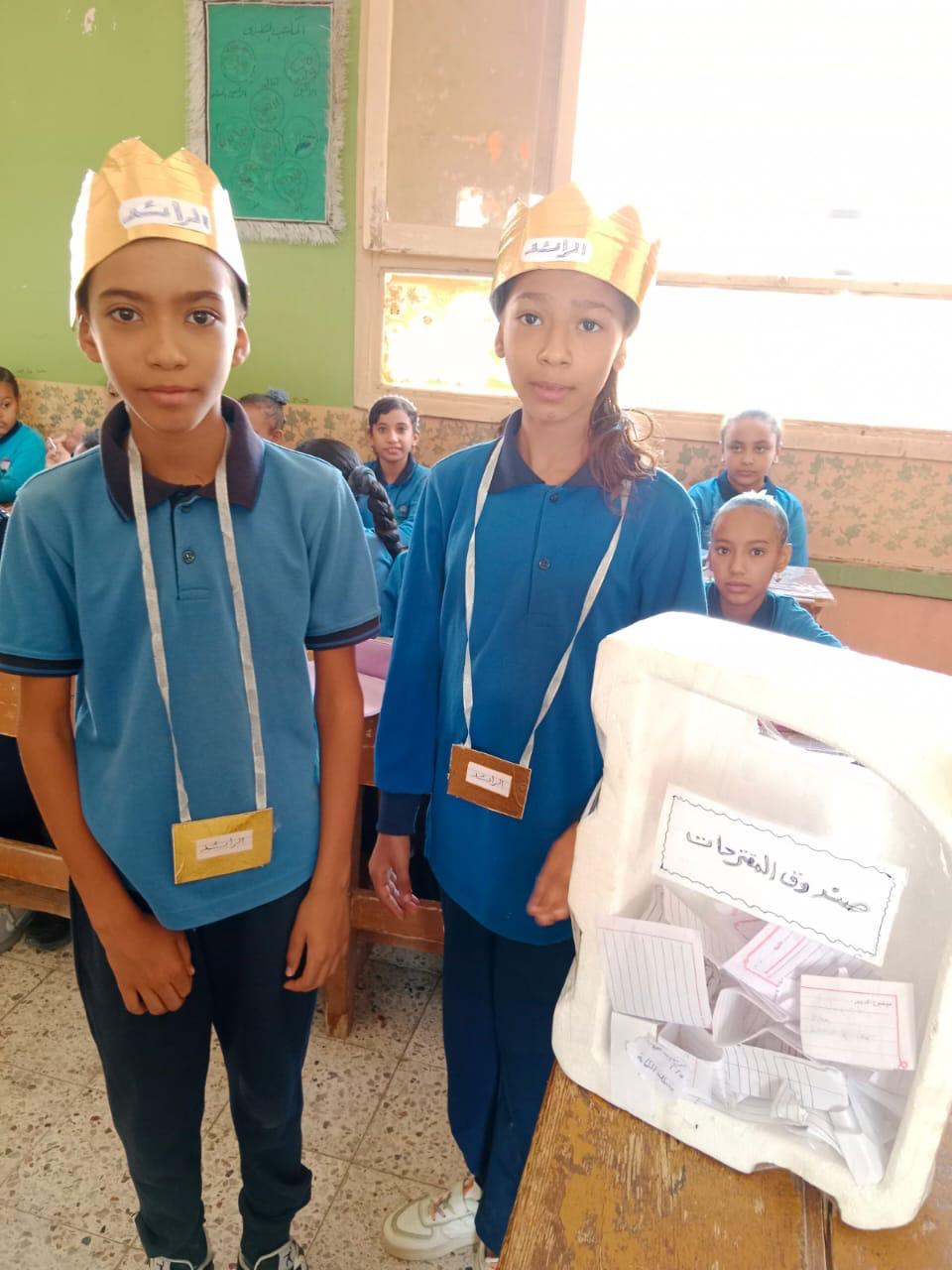

The daily class coordinators take a subject for discussion from the suggestion box. Tokkatsu has been introduced not only in EJS but also in public schools across the country.

The daily class coordinators take a subject for discussion from the suggestion box. Tokkatsu has been introduced not only in EJS but also in public schools across the country. Class discussion: today’s theme is “Celebrating the change of the seasons together”

Class discussion: today’s theme is “Celebrating the change of the seasons together” Cleaning activities at EJS are characterized by the teachers participating with the students

Cleaning activities at EJS are characterized by the teachers participating with the students

Beyond “Technical Assistance”: The Meaning and Responsibility Japan Bears

This project, however, cannot be confined to the framework of simply “exporting excellent educational methods.” It holds profound implications for considering the challenges faced by modern Japan and the world.

Firstly, this is “an expression of trust in the Japanese societal model itself.” Egypt, with its different culture and language, sees in Japanese education a vision for “the future shape of its own society.” At a time when Japan itself is questioned on adapting to diversity, the fact that the Japanese way can become a model for another country offers us Japanese an opportunity to re-examine the value of our own society. And we bear the “responsibility” to maintain a society worthy of their trust.

Secondly, this holds the strategic significance of “building the foundation for peace in the geopolitically crucial region of the Middle East.” In Egypt’s neighboring countries, clashes of values are giving rise to tragic conflicts. Japan cannot intervene directly to bring about political solutions. However, the fact that children are growing up in Egypt, a major Middle Eastern power, learning to acknowledge diversity and find compromise through dialogue – this accumulation will undoubtedly contribute to regional stability in the distant future. As part of Japan’s cooperation, the most fundamental work for preventing future conflicts has already begun here in the educational fields of the Middle East.

Students make onigiri to coincide with Culture Day in Japan

Students make onigiri to coincide with Culture Day in Japan Japanese private companies collaborate in developing the music curriculum

Japanese private companies collaborate in developing the music curriculum

Hints for Overseas Expansion: For the Sake of “Co-Education” that Nurtures the Future Together

Finally, let us consider the implications of Egypt’s Tokkatsu project for the overseas expansion of Japanese education. The following three points can be suggested as hints.

The first hint is to share the “philosophy,” not just the “methods.” The key to success lies not so much in the “activities” themselves, like cleaning or daily Coordinator, but in sharing the underlying social values such as “public-mindedness,” “autonomy,” and “consensus-building,” and redefining them through dialogue within the context of the partner country.

The second hint is to look beyond “short-term results” to “long-term investment.” Social transformation through education takes time. As seen in Egypt, resolve to engage with the system itself, such as by incorporating it into the curriculum, and sustained involvement with an eye on the significant fruits of future peace and stability are indispensable.

And the third hint is for us, the supporters, to continually ask ourselves, “Why are we doing this?” While responding to the partner country’s needs is a prerequisite, each Japanese stakeholder must also persistently ask, “What meaning and responsibility do we Japanese find in this cooperation?” This becomes the source of passion and sustainability, unswayed by short-term societal changes.

In Egyptian classrooms, children strive in their “miniature society.” What they are learning is not merely a Japanese “form.” It is the universal human potential to connect different cultures and build a better future together. The essence of “educational cooperation” lies not in mere technical assistance, but precisely within “co-education” that nurtures the future together. The people of Egypt practicing Tokkatsu are now vividly embodying this fundamental truth before our very eyes.

■Profile of the Author

NAKAJIMA Motoe

Japan International Cooperation Agency(JICA)Expert

Career: In 1995, after graduating from university, he was dispatched to Zambia as a Japan Overseas Cooperation Volunteer (mathematics and science teacher). Upon returning to Japan, he worked as a junior specialist in JICA’s Planning and Evaluation Department, where he was involved in evaluating education projects. He then worked in in-service training for primary and secondary mathematics and science teachers, textbook development, and project management in Honduras and in countries mainly in Africa, including Mozambique, Uganda, and Kenya. Since May 2019, he has served as an expert for the Project for Enhancement and Dissemination of Tokkatsu Model in Egypt, where he oversees the cooperative framework with the Egyptian Ministry of Education and supports the introduction of Japanese-style education in the country.